Why language matters

From pain perception to our memories - word choices influence *everything*

Language matters. But why it matters? That's where things get interesting.

Drawing on research by clever linguistic folk, this post will explain how language can influence our:

thoughts/feelings

actions

memories

We’ll consider its wider effects, too.

Specifically, we’ll look at how language can shape how we perceive:

social issues

physical space

colour

and… bridges

Who are you?

Before we begin, who are you?

I write newsletters that interest me, picturing them landing in equally enthusiastic inboxes.

Realistically, though, there are topics you drag straight to the junk folder. And there are things you’d like me to talk (more) about.

So, I’d love to know a bit about you and what you’re interested in.

Fill out the form to tell me more about yourself.

It took me less than 5 minutes when I tested this myself.

You don’t need to give your name, email address or any personal information if you don’t want to.

This post will still be here when you come back!

Language shapes how we think

Now into the juicy part. (You know, the reason you’re here.)

As I mentioned before: words shape how we think. Profoundly.

They can affect:

1. How we feel

Word choices can shape how we feel - our attitudes to things/people/situations. (More on this later.)

They can also affect how we literally feel in terms of physical sensations.

Has a doctor ever told you, “This might hurt?”

Baruch Krauss published a super duper interesting report about this. Turns out, telling patients that something will hurt is likely to increase their reports of pain.

Telling patients that something will hurt is likely to increase their reports of pain.

In a randomised trial, people receiving epidural or spinal anaesthesia were told:

“Reassuring” words: “We’re going to give you a local anaesthetic that will numb the area, and you’ll be comfortable during the procedure”

“Harsh” words: “You’re going to feel a big bee sting, this is the worst part of the procedure”

The effect? The people who were reassured had lower pain ratings.

2. What we do

Changing just one word can affect our behaviours/actions.

An example? Choosing which job to apply for.

Many of us are socialised to think certain job roles are reserved for certain genders. This can be supported by grammatically gendered language (for instance, Arabic, French, German, Hebrew, Hindi/Urdu, Spanish).

Research shows: girls are more likely to believe they can be engineers if gender-neutral language or both the masculine and feminine forms are used.

For English speakers (or those who don’t speak in grammatically gendered languages), gender-coded words can subliminally dictate which job we apply to.

According to Be Applied,1 women are 50% less likely to consider roles that have a coded gender bias.

3. Our memory

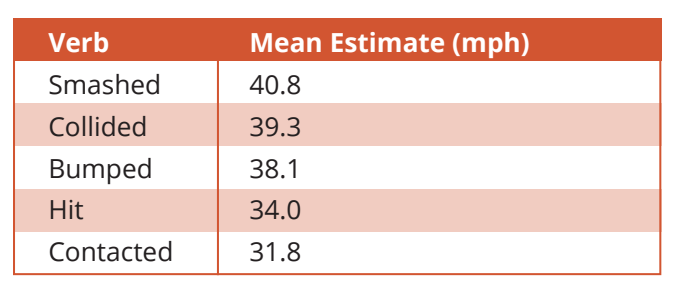

Loftus and Palmer investigated how language choice can affect the accuracy of eyewitness testimony.

45 students watched a film of car crashes.

They were asked questions about the crash using different verbs.

They were then asked to estimate the cars’ speeds.

These people have watched the same video.

But replacing “contacted” with the verb “smashed” speeds up the car by 9mph.

Those words might seem similar. But their meaning is radically different.

Likewise, in a second experiment:

150 students watched the same film.

They were also asked about “broken glass” at the scene.

When the word “smashed” was used, participants wrongly remembered seeing broken glass.

Turns out, leading questions can distort an eyewitness’s memory.

Switching a single word can alter our memories of events.

Switching a single verb can alter our memories of events

Framing crime

We’ve seen how word choices (like verbs) can alter our memories.

Word choices (especially metaphors) can also sway our approach to crime, like the policies we support.

Thibodeau and Boroditsky researched this, by asking 1,482 students to read one of two reports about crime in the fictional city Addison. Then, they were asked to come up with solutions.

One report framed crime as a virus.

The other framed crime as a beast.

These metaphors imply:

Crime is part of a wider issue (virus).

Crime is a single event (beast).

This framing influenced the participants’ solutions.

Participants who imagined a “virus infecting the city” universally suggested:

understanding where the virus was coming from and how it was spreading,

long-term, systemic solutions, like better education and healthcare,

implementing social reforms and prevention measures to decrease the spread of the virus,

educational campaigns to inform residents about how to avoid/deal with the virus.

Participants who imagined a “wild beast preying on a city” universally suggested:

capturing the beast,

caging or killing it,

organise a hunting party to track down the beast.

Now here’s the important bit.

The really important bit.

When the participants were asked which bits of text influenced their decision, the majority circled numbers.

The metaphorical framing effect is covert.

People don’t recognise metaphors as influential in their decisions.

In fact, only 3% of people pinpointed the metaphor as the influencing factor.

The metaphorical framing effect is covert; people don’t recognise metaphors as influential in their decisions.

The power of metaphors

When it comes to crime, public discourse is saturated with metaphors.

Examples include:

crime waves, surges and sprees,

a crime epidemic, plaguing our city, infecting the community,

criminals prey on unsuspecting victims,

hunting for the criminal, tracking and catching them.

As we’ve discovered, metaphors can shape our understanding and reasoning.

This means metaphors can massively impact how we approach social issues.

“We find that even the subtlest instantiation of a metaphor (via a single word) can have a powerful influence over how people attempt to solve social problems like crime and how they gather information to make ‘well-informed’ decisions.” - Thibodeau and Boroditsky

A real case example

Content warning: this section discusses sexual violence Skip to the next paragraph to miss it.

Another Thibodeau and Boroditsky paper investigates a real case of serial sexual violence. Here’s what happened:

A rapist attacked at least 11 girls over 15 months.

During that time, the police had information that could have prevented some of the attacks, if they had shared that information with the community.

But they didn’t share what they knew.

They opted to keep that information secret to set traps for their suspect.

The police were “entrenched in their metaphorical role of hunting down and catching the criminal”.

So much so, they neglected their responsibility to protect the community against further harm.

The girls “were victims… not only of a rapist, but of a metaphor”.

What about other languages?

English speakers use a metaphor roughly every 25 words.

But metaphors aren’t limited to English speakers. Neither are their impacts.

Here’s an example from an extraordinary series by Alpuim and Ehrenberg about the psychology of language. They write:

The German word "Flüchtlingswelle" ("wave of refugees") is one example.

From 2015 onwards, it was often used to describe the refugee movements as a result of the civil war in Syria.

Many political parties and media sources used this term, often.

So readers and listeners to the news (presumably) visualised masses of people rushing in like a wave, again and again.

The metaphor implies a threatening force of nature “to which one is powerlessly exposed”.

What is to be done in the face of such a "wave"? For some, the association is obvious: build dams and protective walls.

Cultural differences

If you’re still unconvinced that language matters, it’s a good time to watch or listen to this short TED Talk (linked below).

In this video, Lera Boroditsky explains how two people (who speak different languages) can witness the same event and remember different things about it.

Boroditsky also shares how languages can shape our perception of:

1. Physical space

Some Aboriginal Australians perceive space and direction in radically different ways from folks who only speak English.

Kuuk Thaayorre people don’t use words like “left” and “right”.

Instead, everything is in “north”, “south”, “east” and “west”.

Everything.

Like, “There’s an ant on your southwest leg.”

If words are “just words” then we wouldn’t expect this practice to change anything essential about how Kuuk Thaayorre approach the world.

But the practice of constantly identifying location using these terms does matter. And Kuuk Thaayorre people are consistently excellent at pointing out north, south, east and west.

(Note: some people have used this to argue that the Sapir-Whorf hypothesis holds. It’s a theory that the words we use completely shape us. It’s used by some people to argue that if a word doesn’t exist in your language then you can never imagine it. I don’t agree with this theory, and think it can cause a lot of damage.)

2. Colours

Some languages have lots of words for colours, some have only a couple of words (like “light and dark”).2

Languages differ in where they put boundaries in between colours too. For instance:

English speakers say “blue” for anything from baby blue to navy blue.

Russian speakers distinguish two tones. For dark blue or navy, “siniy”. For light blue or cyan, “goluboy.”

When you test sighted Russian speakers on their ability to separate light from dark shades of blue, they’re much faster than speakers of other languages.

3. The world around us

In some languages, nouns are assigned a gender (typically masculine or feminine).3

The sun is feminine in German, but masculine in Spanish.

The moon is masculine in German, but feminine in Spanish.

Could this impact how German speakers think about the sun?

The short answer: yes.

The world through gendered language

How would you describe a bridge?

Ask German and Spanish speakers this question, and you’ll likely get dramatically different responses.

“Bridge” is grammatically feminine in German, and grammatically masculine in Spanish, so:

German speakers are more likely to say bridges are “beautiful”, “elegant”, and stereotypically feminine words.

Spanish speakers are more likely to say they’re “strong”, “big” and other stereotypically masculine words.

Assigning different grammatical genders to an object changes how we perceive it.

"It appears that even a small fluke of grammar (the seemingly arbitrary assignment of a noun to be masculine or feminine) can have an effect on how people think about things in the world." - Boroditsky

So, um, language matters

It shapes our thoughts, feelings, actions, memories, responses, and how we see the world.

What now? I’ll soon be sharing a post about why language really bloody matters.

I’ll look at how it shapes society’s attitudes, with a focus on men’s violence against women and girls.

In the meantime, here are some brilliant suggestions from that Bonn Institute article by Alpuim and Ehrenberg:

Pay attention to the exact terms you use to describe something, because it makes a difference.

Ask yourself: what’s the most accurate term for what’s really happening here?

Is it a "demonstration", a "movement", a "protest march", a "riot", "unrest"…?

Are they "students", "kids" or even "climate terrorists" (as they have been called in certain countries)?

Is a company "restructuring", "downsizing" or "firing employees"?

Notice where the spotlight falls. Who are you focusing on?

Did some people get pushed out of the story? Why?

When does the timeline start? For example, I’m writing this on 7 October. It’s the anniversary of the Hamas attacks on Israel. This violence was absolutely horrifying. But the occupation and violence that came before 7 October, and the war crimes that came afterwards, are part of this story too. We must not present one day, or one moment, in isolation.

Ask yourself: who is the active subject?

If there is violence, who’s perpetrating it?

If there is inequity, how did it get created?

Watch out when using “but” and “although”.

Sometimes, using contrasting conjunctions like “but” and “however” to connect two ideas is really useful. Other times, it can be misleading.

Consider this sentence: "She broke her personal record, but it wasn't enough to win the race.” The point of the “but” is to create opposition.

As Alpuim and Ehrenberg explain, conjunctions like “but” can create inaccurate ideas about what solutions are possible, and who is responsible. They can devalue action, or imply that two things are in opposition when they’re not.

Be careful not to present problems as impossible to solve, or different groups as being in opposition.

Ultimately, think very carefully about the concrete meaning of different words and labels.

Tell me about yourself 👋

Fill out this form to tell me a bit about you and your preferences.

It will probably take you less than 5 minutes, and you can keep it anonymous.

The research only mentions “men” and “women” so we can’t be certain, but non-binary and gender non-conforming people may also be put off by masculine-coded language.

The way that languages tend to distinguish colours is not random! It usually follows a set pattern.

To get away from default male thinking in language (and its consequences), Sweden officially adopted a new gender-neutral pronoun in 2015: "hen" (in Swedish, "she" is "hon" and "he" is "han").

So interesting and loved the examples. Really enjoyed this. Xx