The ultimate ADHD-friendly communication guide

A practical and mega detailed guide to use at work

“Ettie, have you heard of ADHD?”

I was 14 and volunteering at a helpline, when one of the psychologists took me to one side.

“Maybe you could look into it, see if any of the traits resonate with you.”

I nodded politely.

Because I knew that ADHD only affects boys.

ADHD meant you couldn’t sit still. But I could sit still. In fact, at that very moment, I was sat in a chair, thinking about all the times I had previously sat in a chair, and therefore definitely not having ADHD.

ADHD meant you were no good at school, didn’t it? But I was academic. I usually aced exams. I got into Mensa (a club for people with a high IQ1). Could an ADHDer do that?

And how could I have a “deficit” of attention? I used to go to the library (for fun), lose track of time and snap back to reality with no idea if I’d been there 5 minutes or an hour. If anything, I felt like I had too much focus, I just couldn’t seem to channel it.

So I plastered a smile on my face, and pretended I was listening.

And now, 21 years later, I think he might have been on to something.2

ADHD isn’t what we’ve been led to believe. I think I’m an ADHDer. And there’s a good chance that you are too, or if you’re not ADHD yourself, then someone you know - someone you live with, work with or care about - is ADHD.

So in this guide, I’m going to share some practical tips for:

writing,

interviewing,

delegating tasks

So that they work better for ADHDers. And in fact, for everyone.3

We’ll cover

Part one: understanding ADHD

Why ADHD-friendly communication is important

What ADHD is (and isn’t)

How to refer to ADHD-ers

Common ADHD struggles

Part two: how to be an ADHD-friendly communicator

We’ll focus on four areas that tend to be an issue for ADHDers (but which will benefit everyone).

Time agnosia: be specific

Paying attention: keep it punchy

Working memory: repeat, repeat, repeat

Emotional regulation: clarity and context

Part one: what ADHD is

1. ADHD friendly comms is better comms

Becoming a more ADHD friendly communicator benefits everyone. Side effects may include:

copy that’s even easier to scan,

calls to action that are even easier to follow, and

more succinct conversations.

You’ll never regret adapting your communications to be ADHD-friendly.

It’s about respecting people’s time, energy and attention. Why would you NOT want to do that? it’s just better communication.

You’ll never regret adapting your communications to be ADHD-friendly.

2. What even is ADHD

ADHD stands for attention deficit hyperactivity disorder.

It needs a rebrand.

Attention Deficit? Nope.

ADHD-ers have a lot of attention channelled through an interest-based nervous systemHyperactivity? Nope

There are three types of ADHD, including ‘inattentive’, ‘hyperactive’ and ‘combined’.

And hyperactivity isn’t always displayed externally, like being unable to sit still. Hyperactivity can be internal, such as through racing thoughts.A disorder?

Let’s get into that.

As doctors Edward Hallowell and Dr John Ratey explain:

”ADHD is an inaccurate — and potentially corrosive — name.

The term “deficit disorder” places ADHD in the realm of pathology, or disease.

Individuals with ADHD do not have a disease, nor do they have a deficit of attention; in fact, what they have is an abundance of attention. The challenge is controlling it.”

Individuals with ADHD do not have a disease, nor do they have a deficit of attention; in fact, what they have is an abundance of attention.

ADHDers have plenty of attention

As Hallowell and Ratey say:

“A more accurate descriptive term is “variable attention stimulus trait” (VAST), a name that allows us to “de-medicalize” ADHD and focus instead on the huge benefits of having an ADHD brain.”

Check out their article, ADHD needs a better name: we have one, to learn more.

ADHD is a neurotype

ADHD is a neurotype. A way that brains can be.

It’s not wrong. Just like being short or tall is not wrong.

“A lot of the things we’ve been told are deficits are actually just differences. We’re not lacking; we just do things a little differently.” - Ellie Middleton, ‘Unmasked’

3. How to refer to ADHD-ers

Why many of us use identity-first language

A lot of ADHDers use identity-first language.

(Not all, just a lot of us).

That sounds like:

“I am ADHD” instead of “I have ADHD.”

“ADHD-ers” not “people with ADHD.”

Why do many ADHDers use identity-first language?

ADHD is for life

“Have” can imply a passing state. But ADHD is like any other neurotype, and most neurodevelopmental conditions. It’s not a phase. You don’t grow out of it.

ADHD is part of us

We don’t say that parents are experiencing offspringness. We say they are parents. We don’t say that people from France have Frenchness. We say they are French.

“An identity is not something that I have. It is who I am” - Lydia X. Z. Brown

ADHD is not shameful

“Have” can suggest something is bad or shameful - otherwise why try to separate me from it? This applies to so many other identities.

Lydia X. Z. Brown says it wonderfully, when talking about autism:

“When we say “person with autism,” we say that it is unfortunate and an accident that a person is Autistic. We affirm that the person has value and worth, and that autism is entirely separate from what gives him or her value and worth. In fact, we are saying that autism is detrimental to value and worth as a person, which is why we separate the condition with the word “with” or “has.” Ultimately, what we are saying when we say “person with autism” is that the person would be better off if not Autistic.” - Lydia X. Z. Brown.

ADHD is part of who I am. I do plenty of things that make me feel ashamed.4 But being an ADHD-er is not in itself shameful.

ADHD is part of who I am. I do plenty of things that make me feel ashamed. But being an ADHD-er is not in itself shameful

No shade if you choose person-first language (“people with ADHD”, or “I have ADHD”).

Everyone’s different.

If you’re talking to or about someone, always ask them.

Diagnosis isn’t available to everyone

If you advertise a service for “those diagnosed with ADHD", who are you reaching?

(Not me, who’s waited 21 years to look into this ADHD thing.)

If you say it’s for ADHDers, you’re including people who connect with the identity but may not have the piece of paper.5

Self-diagnosis is valid, because:

diagnostic standards are biased (and outdated), having long been based on research focused on young white boys,

some diagnoses can put people at risk (for example, people can be denied gender affirming care or banned from moving to certain countries if they are diagnosed as autistic),

waiting times for ADHD assessments can last years,

private assessments can be expensive (in the UK, private assessments typically cost around £1000).

Self-diagnosis is valid, and it’s often essential.

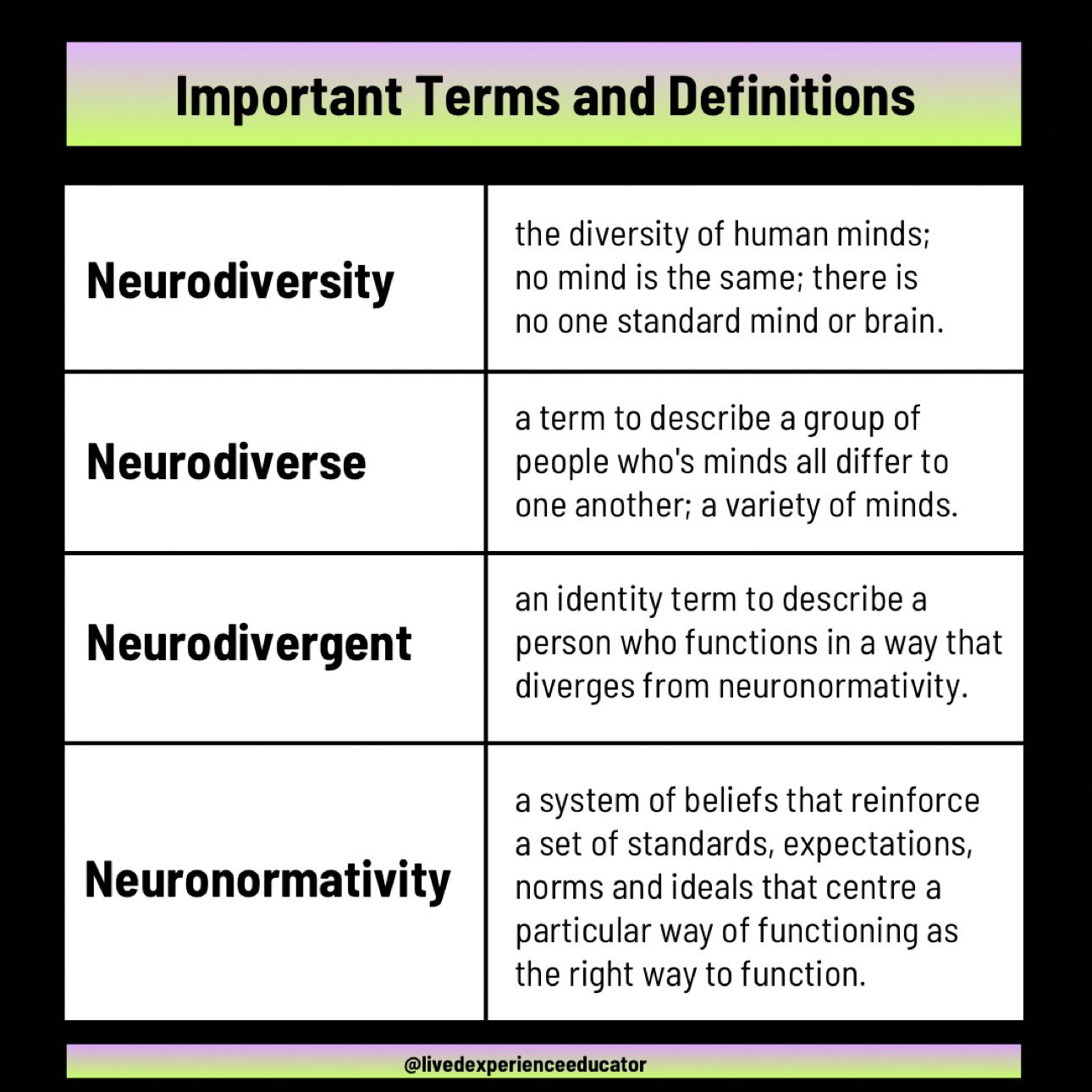

Talking about neurodivergent people

Sometimes, I see ‘neurodiverse’ and ‘neurodivergent’ used interchangeably.

Or people talk about neurodivergence when they mean only ADHD or autism, forgetting about identities, differences and conditions like:

dyslexia

dyspraxia

OCD

PTSD

bipolar

epilepsy

schizophrenia

and many others (including those listed in this graphic from the incredible Sonny Jane Wise).

Some useful terms, from Sonny Jane Wise:

And here are some examples in sentences:

“Diversity isn’t limited to visible characteristics; neurodiversity at work is also important”

“Our greatest asset? Our neurodiverse team”

“I am neurodivergent, so I need these reasonable adjustments”

“Neurodivergent folk often prefer to use identity-first language”

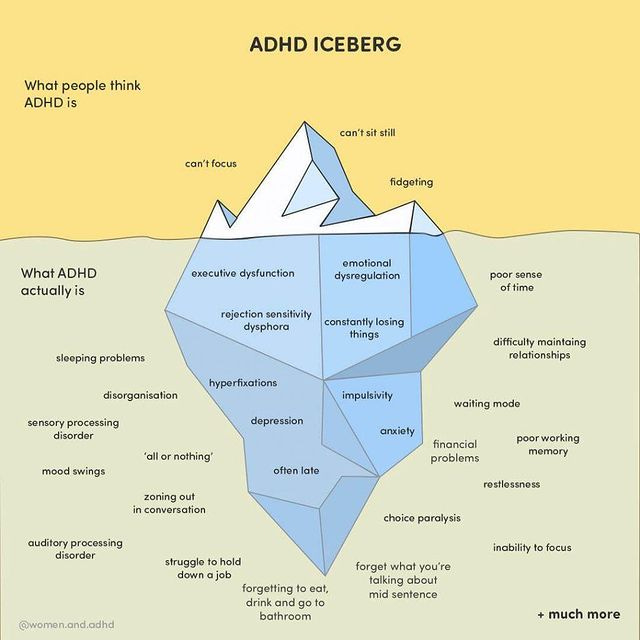

4. ADHD struggles

ADHD-ers may find it tricky to:

manage time

stay organised

follow instructions

prioritise/complete tasks

cope with stress

regulate our emotions

maintain (healthy) relationships.

Regardless of what LinkedIn might have you believe:

ADHD isn’t a superpower.

(If it feels that way for you then I’m genuinely overjoyed for you, but I don’t think you should get to set the narrative for how ADHD is understood. Because not everyone experiences it a blessing).

The superpower myth fetishises Disabled and neurodivergent people, and leaves us without vital support.

[Content warning: brief mention of suicide and addiction]

ADHDers are:

30% more likely to have ongoing employment issues,

5 times more likely to try to kill ourselves,

5 to 10 times more likely to experience alcohol addiction,

The superpower myth has real consequences. It praises us, while denying us the support we need.

Our words matter. When we understand ADHD better, we can speak more clearly about it, and give ADHDers (and everyone) the support they need.

Part two: ADHD-friendly communication tips

ADHD presents differently in different people. I’ve picked four (out of many) common ways it shows up, and suggested some practical tips you can try.

1. Time agnosia: be specific

It’s 8.45 am. I want to send this out at 9. So I think I’ll quickly bake a cake, walk the dog and file my taxes, before I hit send. Hmm. Ambitious? Maybe I’ll just bake the cake.

ADHDers often struggle with time: keeping track of it, noticing it passing, planning how to use it.

It’s called time agnosia (or time blindness).6

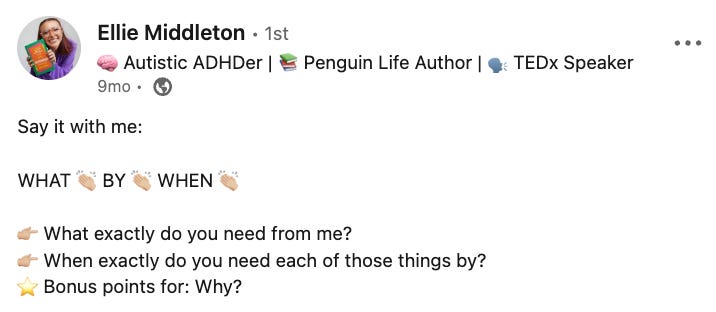

Instructions: what by when and why

When giving instructions to a colleague, follow this framework - outlined by the wonderful Ellie Middleton: what by when and why.

It goes like:

What exactly do you need from me?

When exactly do you need each of these things by?

Why?

So you might email a colleague:

Please fill out your weekly reflection form by 2pm on Friday. That way, we can discuss your ideas in our 1:1 meeting on Monday.

The ‘why’ part can be especially important for autistic people.7 But only if it’s short, clear and relevant.

Indicate the level of urgency

Any time my phone pings, I assume it’s urgent.8

Because ADHDers tend to experience time as either “now” or “not now.”

Extra especially if someone asks for something “soon.” If they want it “ASAP”, I probably won’t eat or sleep until it’s done.

That’s why it’s useful to open requests with a brief indication of how important the message is:

“For Monday”

“Open after your holiday”

“Non-urgent request”

“Top priority for next week”

Oh, and try not to send emails on weekends, at night, or when your colleague’s on holiday.

You can schedule emails to send later.

Keep calls to action clear

When it comes to compelling calls to action, clarity is key.

Set a specific deadline.

Make sure it’s not too far away. Test this out. 7 days notice might be too long and stressful for some people. 24 hours might be too short for others.

Remind us. Remember when I said there was “now” and “not now”? If I don’t do something right away, I may never do it. Automated follow-up reminders are lifesavers.

Keep it concise. “Want to save 20% on your purchase? Shop now - link in bio. Offer ends 5pm on Sunday 18th May.”

Explain the next step

What’s the next step, and why should I take it?

“Learn more” → “Read more case studies”

”Submit” → “Start my free trial now”

”Subscribe” → “Access weekly insights”

(These examples are more accessible to screenreader users, and they’re way more persuasive, too!)

Make forms friendlier

To make it easier for ADHDers to fill out your forms, try including:

An option to save progress, and return to the form later.

Automated reminders to nudge people to come back.

A progress bar to keep users informed about where they’re at and how long the task will take them.

And please, don’t ask for anything you don’t really need. Like my “landline number.” (Again, this is just decent user experience - it’s not unique to ADHD).

Every additional word, every extra question, is just heaping up the likelihood that I will never fill this form out. And while I’m trying to fill this form out, my dinner is burning, my dog is barking and I really think I’m meant too be somewhere right now, I just can’t remember where.

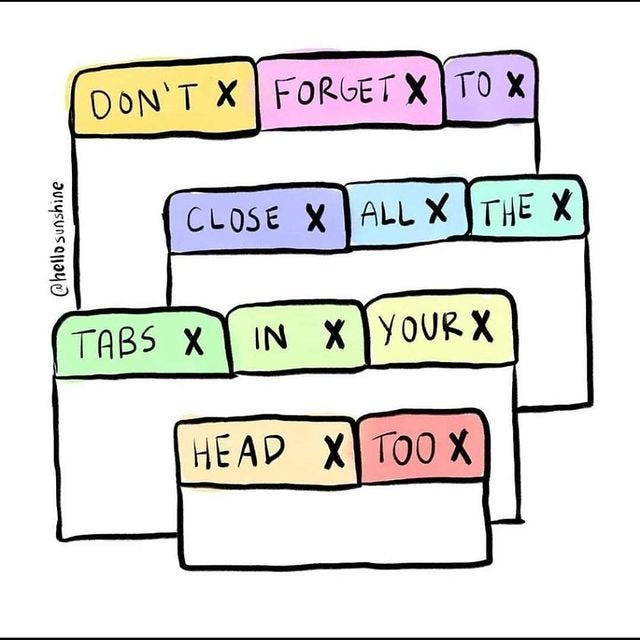

2. Paying attention: keep it punchy

Get to the point.

Choose short and simple words.

Put them into short and simple sentences.

To create short and simple paragraphs.

Check out my article “simple writing is better writing” for practical tips:

Write for skim readers

73% of people skim-read blogposts. Users typically read just 20% of a webpage’s content.

Don’t write for a focused, well-rested person sat at a laptop.

Write for the frazzled, stressed-out person who’s trying to read your email on her phone as she cooks a risotto while she joins a Zoom call, pays her library fines and searches for her slippers because she knows she left them somewhere. (Once again, it’s me, hi).

Use short words.

Don’t use a short word if you’ll lose important nuance. But if you possibly can then favour brevity over sesquipedalian utterances.

Sorry I mean: if there’s a shorter word that does the job just as well (like “use” instead of “utilise”, then go ahead and

utiliseuse it)

Be literal.

Elaborate metaphors, niche cultural references and obscure idioms take more time and effort to detangle.

Say exactly what you mean (or give a literal explanation before or afterwards to explain what you meant).

Replace adverbs with strong verbs.

"She walked slowly towards the door" → "She traipsed towards the door."

Stick to short sentences.

Aim for no more than 25 words in a sentence.9

That doesn’t mean writing like a robot. Vary your sentence length, and sprinkle in longer words whenever a short word can’t do the job.

Read your work aloud. Would a human actually say that? Perfect, your writing flows. No? Try saying it out loud, then write that instead.

Keep paragraphs to just a few sentences.

One idea per paragraph.

That’s it. That’s the point.

Use meaningful headings and subheadings.

Meaningful headings and subheadings actually tell you something. Like “urgency” just tells you the topic. But “indicate the level of urgency” makes a specific point. A skim read tells you the main message (if you’re sighted, you might scan by visually reading; if you’re blind or partially sighted, you might scan by listening to the subheadings).

Use lists.

Oh my gosh I love bullet points.

They’re so effective.

For sighted readers, they’re easy to scan, easy to navigate, and easy to absorb.

Include visual elements.

Like images or illustrations.

This webpage on gov.uk is a brilliant example of ADHD-friendly copy:

Struggling to remember all of that? Bookmark Hemingway Editor - use it to check your copy. It’ll highlight spots to simplify.

Format properly

Accessible writing isn’t just about word choices and paragraph structures. Style affects readability too, particularly for dyslexic people.

To make sure your copy is readable:

use a standard font in minimum size 12 (I always use sans serif fonts, but sans serif fonts are not always easier to read)

left align text

avoid multiple columns (like in newspapers)

include plenty of blank space

use larger (1.5) line spacing

stick to sentence case

make sure hyperlinks stand out

use bold font to highlight text (avoid underlining or too many italics).

Onboarding colleagues: have a structure

Welcoming a new team member?

Send a “before you start” email, and try to cover:

What hours they’ll work

Where they’ll work

How you access the building (Can someone meet them outside?)

The dress code

How breaks work (fixed time? How long is lunch? Is there a kitchen?)

Some (probably neurotypical) new joiners will find this information obvious. That’s okay! You won’t harm them by giving them this information. And it can really help neurodivergent people.

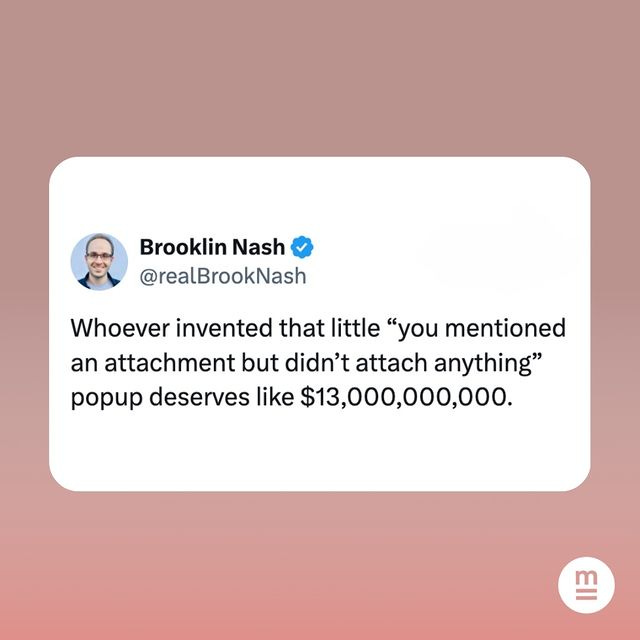

3. Working memory: repeat, repeat, repeat

Working memory is the brain’s short-term storage space.

Working memory affects a lot of things, including how we:

process and store information

follow instructions.

ADHD affects working memory (in most people).

And it can make “small” tasks like remembering to take medication every day feel nearly impossible.

So try to set people up for success.

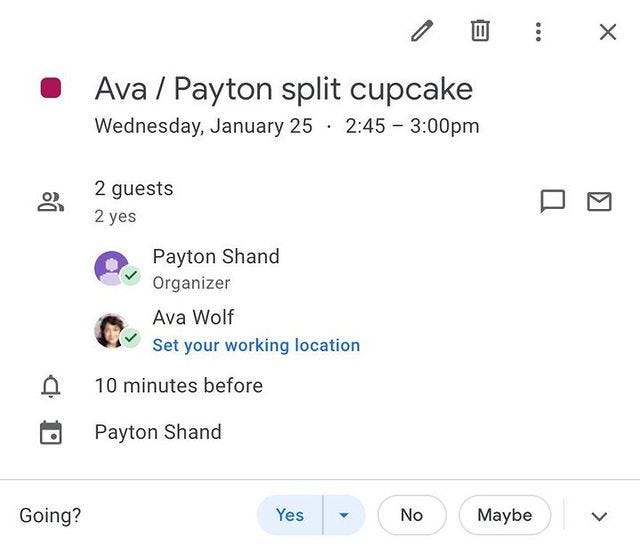

Meetings: agendas and follow-ups

Remind people

Not in a passive aggressive “let’s not forget this deadline shall we Miranda? I know you’re terrible at timekeeping” kind of way.

Just send reminders before important events or deadlines, as standard.

Schedule meetings in advance

Last-minute schedule changes can be super stressful.

If possible, book meetings days or weeks in advance.

Allow buffer time

Neurodivergent people often find transitions between tasks difficult.

Keep buffer time in between meetings, and don’t expect everyone to be able to jump quickly from one task to another.

Only have necessary meetings

You can use Loom for short tutorials/videos.

Set aside the actual time you need (don’t book in an hour for a quick catch-up).

Share an agenda

Set an agenda. Stick to it.

Include a topic, location, attendees and discussion points.

Include a buffer time for topic-switching.

Share a brief recap.

Include:

Clear action points.

Specific deadlines.

The person responsible for each task.

A transcript (if virtual), using software like OtterPilot.ai.

Instructions: cover all bases

Along with the “what by when and why” framework, try giving instructions:

written down and out loud, so people can check they understood them right (I find my Otter Pilot an amazing help for this as it records all my calls and transcribes them),

with specific requests: avoid using abstract language/jargon, like, “Let’s touch base on this project.” Instead, you could ask, “How much progress did you make on this project last week? Would it be helpful if we talk through your main priorities today?”

with clear expectations about the quality, length, urgency, and so on.

in clear, simple steps. “Give everybody a copy of this” could become “Make three photocopies of this, and give one each to Sam, Mary and Ahmed.”

Interview questions: let neurodivergent folk shine

Give interview questions in advance.

Best-selling author Leanne Maskell advocates this, as questions in advance help “avoid unnecessary anxiety that helps nobody.” (Amen.)

Avoid open questions.

“Tell me about yourself” doesn’t tell the interviewee much. What are you actually looking for here?

Open questions can make it tricky to stay on topic, too.

You could say, “Tell me about the jobs and/or voluntary work you’ve done in the past three years, and how the skills you developed would be relevant for this role.”

Ask for examples.

Hypothetical questions like, “How would you cope if a customer asked you for help when you’re busy?” turn my brain to soup.

A better question could be, “In your last job, how did you respond to clients asking for help during busy periods?”

4. Emotional regulation: context and clarity

Rejective Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) is the “inability to regulate your emotional response” to rejection (whether real or perceived).

For many neurodivergent folks, getting criticism - even fair constructive criticism - can feel agonising.

Some of us are also terrified of disappointing other people. It can make us nearly incapable of saying no.

So intense is the anguish that we feel when other people say no to us, that we will turn ourselves inside out so as not to say no to somebody else.

1 in 3 people say Rejection Sensitive Dysphoria (RSD) is the hardest part of living with ADHD.

We try to prevent RSD by:

holding ourselves to unrealistic standards

people-pleasing

avoiding “no” at all costs

becoming perfectionists.

The result? Anxiety. Masking. Burnout.

So how can you avoid triggering RSD?

Meetings: give context

Avoid asking, “Can we have a chat?” or saying, “I’ve got some news.”

This can be super anxiety-inducing. Instead, it’s important to:

Avoid last-minute meetings

Also, many ADHDers hate unscheduled phone calls. An unexpected phone call stresses me out enormously. I’ll pick up because I genuinely assume someone has died. And then feel relieved (no one died) and disappointed (you put me through all this stress for nothing).Share why you want to talk. For instance, “I’d love to brainstorm ideas about this project,” or, “A client has given us some positive feedback that I’d love to share with you!”

If the reason is negative, share plenty of information before the meeting. Give the person space to process.

Provide reassurance.

1:1 support: make it easy

(Content warning: brief mention of drowning.)

When I was younger, I got washed out to sea and had to be rescued by a lifeguard on a surf board.

Except, the first time he yelled at me to get on the surfboard I said “no thank you.”

The second time I said “really, I’m fine.”

The third time he yelled at me, I got on the surfboard and thanks to this, I am alive.

Please don’t think that all ADHDers refuse life rafts.

But we often struggle with asking for and accepting help when we need it.

Often, ADHD-ers struggle to know when - or how - to ask for help. Make it easy for ADHDers, and all the humans you work with, to get help.

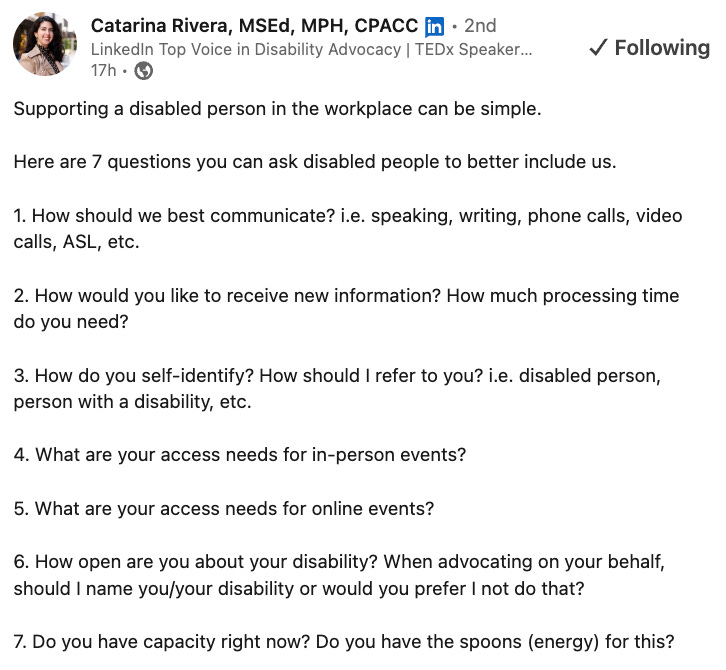

Get to know how they work best.

Ask people what helps them work effectively (you could use a tool like Manual of Me to share yours)

Check in regularly on people’s stress levels: what’s on their to-do list? Is it realistic? What can you take away?

Find out what the warning signs are: how will you know someone is approaching burnout?

Proactively offer support, and keep adjusting it in line with the support people say they want.

Make it okay to say no

Like, really okay. You can literally say “Could you do this for me before Friday? It’s okay if you can’t.”

Model boundaries

I used to feel like colleagues with kids could say no to things, because they had “proper” reasons. But I didn’t have legitimate reasons to say no to requests.

If you can, model that it’s normal to push back on requests, for “trivial” reasons like needing food, water and sleep.

Model receiving help

If you can ask for and receive help without your skin crawling, congratulations!

Keep doing it. Be visible.

Scheduling weekly check-ins.

Stick to the same day and time where possible.

Check-in with your team’s capacity and workload regularly. (50% of neurodivergent employees feel burnt out at work.)

“How are you managing your workload this week?”

“Has anything been worrying you at work recently?”

“Do you have the resources you need to meet your goals?”

“How can the team better support each other?”

Make it easy to ask for help, perhaps by sending your Calendly link at the start of each week, or having it readily available in your team’s communication channel.

Set SMART (specific, measurable, achievable, realistic, timebound) goals with clearly defined expectations.

Break down any bigger projects into manageable tasks.

Ask people (but don’t put them on the spot)

For instance:

“I was wondering if you’d be interested in owning this project. Have a think, and let me know by Friday morning.”

“I’d love to have a reading group at work, and I think you’d be brilliant at running it. If you could think about whether you’d have the capacity (or would be interested), we can chat more in our 1:1 meeting. No worries if you can’t take it on!”

Listen (actively).

Leanne Maskell’s book, ‘ADHD Works at Work’, covers five steps to take when an ADHD-er is struggling at work:

Reassure: “Thank you for sharing this with me, I know it can be hard to ask for help. I’m here to support you without judgment.”

Listen: “What would be a good outcome? How can I best support you?”

Explore: “What would you like to be different? What’s worked before? What barriers are in your way? What steps do you need to take to do this?”

Signpost: “What support do you have in place? What resources are available to you?” (Access to Work could be a good pointer!)

Filter: “What actions would you like to take away from, today? Would you like me to follow up on those next week?”

Feedback: be prompt

Try not to give your colleagues time to stew on worries.

Respond promptly.

Acknowledge when you’ve received work (verbally, written, or both).

If you’re not reviewing the work yet, say when you will. For example:

“Thank you for sending this report. I’ve had a glance, and the statistics look really impressive. I’ll have a thorough read this evening, and I’ll get back to you before Thursday with any comments and suggestions.”

Praise in public.

Acknowledge achievements in team meetings.

Be specific about what the person has done well.

When you have constructive criticism, I’d generally suggest you offer it privately (1:1).

“Constructive” = specific + clear.

Feedback is a gift. But it can be incredibly painful for some people. Avoid triggering RSD by:

Focusing on the situation/project, not on the individual.

Giving context - explaining why this matters.

Being open to their suggestions and solutions.

Asking clarifying questions.

Giving clear action points.

For example, instead of saying, “You included too much jargon in the report,” you could say:

“This report was really detailed - I’m super impressed by [example]! In the first section, I spotted two niche terms: [example] and [example]. This might not mean much to our client, who doesn’t work in our industry. To make sure they understand the great work you’ve been doing, what other terms could we use here?”

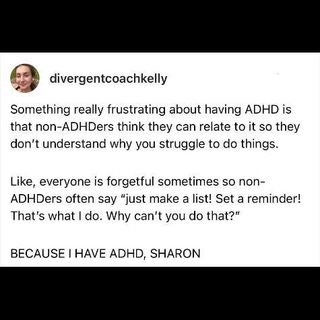

Watch out for well-meaning advice

If you’re not ADHD yourself (and even if you are or think you might be), watch out for well-intentioned advice.

Almost nobody needs the advice “just buy a planner”, “just try time-blocking” or “just break your tasks down into smaller tasks.”

It’s not that these aren’t useful. Of course, they are part of the strategies that can help us manage our ADHD.

For example, I love Goblin tools, an AI assistant that helps you break down tasks into smaller ones.

But telling someone how to live their life is rarely helpful.

I’ve tried every productivity tool I’ve ever heard of. Sometimes, many times. I have more planners than there are days in the week.

ADHDers don’t need to “just” do anything. (Many people consider words like “just”, “simply”, “quick and easy” to be a microaggression).

We don’t need to act more neurotypical, to cover up our traits or stop being our selves.

We need to be accepted, supported and allowed to find our own ways of living.

Neuro-inclusion doesn’t need to be complicated.

Start simple. Pick something practical from the list, and try it out.

What will you start with? Let me know in the comments!

Want to become an inclusive and accessible communicator?

You’re still reading! Amazing. If you didn’t know, I’m Ettie - an award-winning inclusive and accessible communication educator.

I deliver joyful and practical workshops and training programmes. You can:

hire me to speak to your team: I design everything bespoke, from short lunch-hour talks to multi-part training

join Bold Type, my 12-week programme, where I’ll teach you everything I know about inclusive language and accessible communication.

Aged 14, I thought being in Mensa sounded cool. Aged 33, I think IQ tests measure the ability to do an IQ test. They’re nearly meaningless. They are designed to favour the most privileged. And they have a disturbing racist past. So no, I am no longer a member.

Self-diagnosis is valid. But I want an official assessment. To do that, I have to hand the forms in. (I lost them, got new ones, filled them out but didn’t take them back to the doctors, took them back last year, found out there was another form, and now that form is sitting on my hall table). The process for getting an ADHD assessment in the UK is not ADHD-friendly.

Not in that “everyone has ADHD these days” (non)sense. But because ADHD-friendly communication just means being clear, concise and to-the point. It’ll work better for ADHDers. But also for tired, anxious, distracted folks. AKA literally everyone I know.

Very rude of you to read this footnote about my shame but while you’re here let me tell you about the time I was charged, and paid, over £1000 in late payment fees for failing to file a tax return. What made it even worse was that this was for a year when I didn’t earn enough money to actually pay tax. I was just supposed to file the tax return to let them know that I hadn’t earned enough money. Weep weep. ADHDers are estimated to pay at least £1600 a year in “ADHD tax” from costs like forgotten subscriptions, expired food and impulsive decisions. I think it’s much, much more expensive than that TBH.

Somewhere between 30 to 70% of ADHDers are also autistic. And many autistic people are literal thinkers. I often don’t realise that I’m eligible for opportunities, because I take the criteria extremely literally. So set the criteria as broadly and generously as possible.

As Sonny Jane Wise (@LivedExperienceEducator) points out, “time blindness” is an ableist term that many blind people have asked us to stop using. Consider saying “time agnosia” or “difference in time perception” instead.

50-70% of autistic people are also ADHD (Front Psychiatry, 2022).

This isn’t just the case for distracted ADHDers. For example, folks in junior roles - eager to prove themselves - might respond like this, too.

Try chopping out words like: just, never, always, actually, absolutely, really, completely, very, literally, genuinely, simply, only. “That are” is a sneaky one to watch out for, too!

Thank you so much @Sabine Harnau!

Not yet but I would like to make one for autism for sure!

Some folks who share absolutely brilliant resources include:

https://www.thearticulateautistic.com/

https://www.instagram.com/blackspectrumscholar/?hl=en

https://lovettejallow.substack.com/

And this one is Lydia X.Z Brown’s old blog, hasn’t been updated in a while but still has some great stuff:

https://www.autistichoya.com/

Thank you for this post Ettie, I feel seen.

I had a question about the last example in point 9 - how does someone use ‘that are’ as a micro aggression? I’m also curious where you stand with numbers in a table for a technical report - I find numbers from 1 to 10 are easier to read as numerals among other numerals with units but many house styles suggest spelling them out as one, two etc